Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi recently promised to restart visits for former residents to the Northern Territories, islands now under Russian control. Seen as a revival of frozen humanitarian exchanges, she stressed the urgency during a meeting with Hokkaido Governor Naomichi Suzuki and former islanders. Many of those displaced are now over 88 years old, making this a pressing issue.

On February 7, 2025, Japan marked “Northern Territories Day.” The date traces back to the 1855 Treaty of Commerce and Friendship between Japan and Russia, which first set the border and placed the islands south of Etorofu under Japanese sovereignty. Today, the day serves as a reminder that the four islands—Habomai, Shikotan, Kunashiri, and Etorofu—remain under what Japan calls “illegal occupation” by Russia.

The islands’ status was already defined in the mid-19th century. The 1855 treaty drew the border between Etorofu and Urup, clearly placing the four islands under Japan’s jurisdiction.

By the late 18th century, the Edo shogunate had begun developing the islands. Fishermen from Matsumae settled there, and Takadaya Kahei promoted marine industries, gradually forming Japanese communities.

After the Meiji Restoration, Japan expanded governance, building schools and hospitals while developing forestry, fisheries, and mining. The islands were never foreign territory; Japan has always considered them part of its homeland.

The turning point came at the end of World War II. Despite the 1941 Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan on August 9, 1945.

Soviet troops advanced quickly, seizing Shumshu at the northern tip of the Kurils on August 18, then landing across the Northern Territories between August 28 and September 5. At the time, about 17,000 residents lived there—all Japanese, with no Soviet settlers.

Even after Japan’s surrender on September 2, the Soviets pressed on. In January 1946, they declared the islands part of the Soviet Union. By 1948, all Japanese residents had been forcibly repatriated.

The 1945 Potsdam Declaration confirmed the Cairo Declaration but did not address the islands. The 1951 San Francisco Treaty required Japan to renounce the Kurils, but left the definition vague. Japan insists the four islands were excluded. The Soviet Union refused to sign, leaving the two nations without a peace treaty.

⬆ Soviet troops landing on Shumshu in the Kurils

Japan protested repeatedly in the postwar years.

In 1956, the Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration was signed, restoring diplomatic ties. Moscow agreed to return Habomai and Shikotan once a peace treaty was signed.

But Cold War tensions stalled talks. The Soviets cited the 1945 Yalta Agreement, a secret deal with the U.S. and U.K. Granting them the Kurils. Japan dismissed it as invalid.

Later agreements in 1991 and 1993 reaffirmed the islands as the core territorial issue. After the Soviet collapse, Russia held firm, calling the islands a legitimate outcome of World War II and refusing to return them.

Today, the islands fall under Russia’s Sakhalin administration, home to about 18,000 residents, mostly Russian.

Satellite images after the 2022 Ukraine war show new hotels, hot springs, and expanded ports. Fish processing plants now export to Korea and China. Schools and hospitals have grown too. Fishing remains the backbone, with the surrounding waters among the world’s richest due to the meeting of the Oyashio and Kuroshio currents.

⬆ Runway on Kunashiri Island

Russia treats the islands as strategic, stationing a division with tanks, missiles, and drones. Military bases have been steadily reinforced.

For Japanese people, the islands are ancestral land. Former residents now average over 88 years old. Many trace roots to Toyama fishermen who once saw the islands as a place of opportunity.

Since 1992, Japan and Russia have run “visa-free exchanges,” letting former residents visit graves and foster dialogue. COVID-19 halted the program in 2020, and the Ukraine war froze it completely. Japan also banned investment in the islands to signal non-recognition of Russian control.

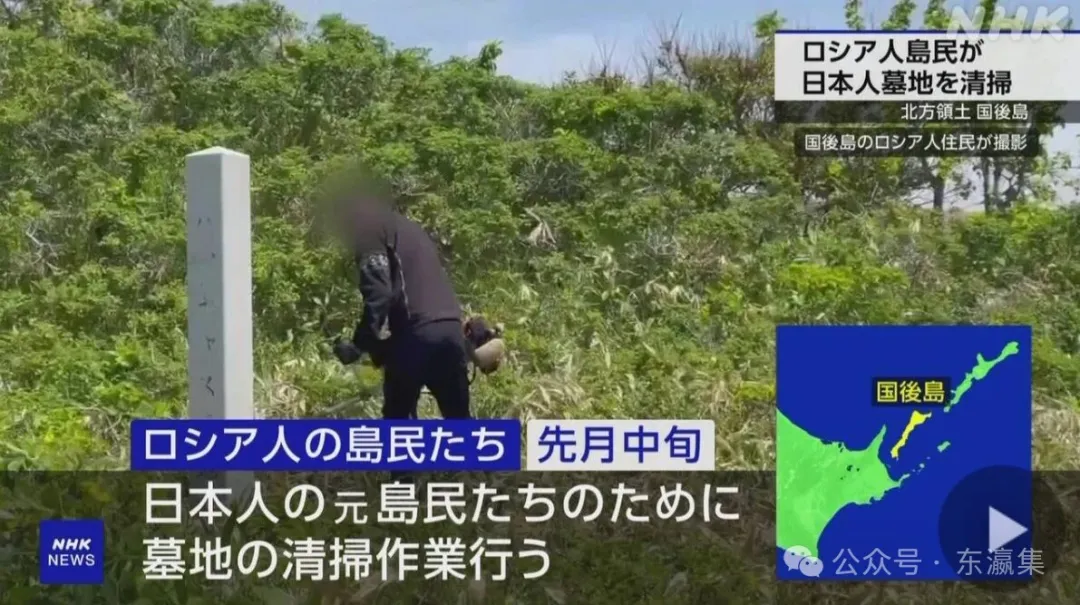

⬆ Kunashiri residents tending former Japanese graves

Japan’s stance remains clear: the islands are inherent territory. Textbooks must state they are “illegally occupied.” Russia calls them the “Southern Kurils,” a rightful prize of WWII, and refuses to return them.

A 2025 Cabinet survey showed that half of the Japanese under 30 don’t know the current status of the Northern Territories. NHK profiled families of former residents gazing across the Nemuro Strait, saying, “Distance isn’t the barrier—politics is.”

Japan promotes awareness through school lectures and social media skits. Russia counters with patriotic education, reenacting Soviet victories. Most residents believe there’s no reason to hand the islands back.

The real solution lies in a peace treaty. But with the shadow of the Ukraine war, negotiations look far off. The United States and other allies back Japan’s stance, pointing to international law that says “illegal occupation creates no rights.” That principle could become Tokyo’s bargaining chip.

Eight decades have passed, yet the lighthouse beams on these islands still cut through the fog. The Northern Territories aren’t just dusty history—they’re living memories shared by two nations. Whether they become a bridge for reconciliation or remain a permanent divide is still an open question.

References:

https://hoppou.blog/kunashiri-107/

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8D%A0%E5%AE%88%E5%B3%B6%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84