Walk through the busy streets of Tokyo or Osaka, and the smell of Korean barbecue is everywhere. But behind that familiar aroma lies a century-long story of families who endured both joy and hardship for generations.

Picture a typical Japanese office worker. His surname sounds completely Japanese, yet at home he speaks Korean with his parents. Their children learn the language in school, wear traditional attire, and dance to old folk songs. On weekends, the family heads to Tsuruhashi, Osaka, to shop for kimchi and hanbok, and immerse themselves in a "homeland" atmosphere that feels both close and far away.

This is not a quick taste of K-culture for a tourist. These are Zainichi Koreans – people living in Japan with strong roots in the Korean Peninsula. Approximately 400,000 to 500,000 people call Japan home, making them one of the country's most unique but often neglected minority groups.

Special Permanent Residents: A Status Just Below Citizenship

If you've ever entered Japan, you may have noticed a lane marked for Japanese citizens as well as "Special Permanent Residents." so what does that mean?

This situation is unique to Japan. It was built for Koreans and their descendants who came during the colonial period. It grants almost the same rights as citizens – unlimited migration, no re-entry permits – but without the right to vote. Compared to regular permanent residents, their status is more secure, although it carries heavy historical burdens.

By the end of 2024, Japan's Ministry of Justice reported approximately 274,000 special permanent residents, accounting for 7.3% of all foreign residents. Roughly 98% hold South Korean nationality, while only a small portion are registered as North Korean.

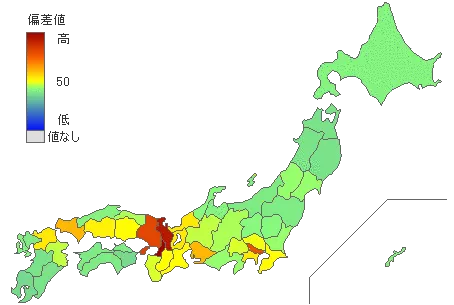

Zainichi Koreans are concentrated in major cities:

- Osaka: the largest community, with more than 1 in 100 residents (national average is 0.3–0.4).

- Kyoto, Hyogo, and Tokyo follow, with Kansai accounting for nearly half.

- Classic hubs include Osaka’s Tsuruhashi and Tokyo’s Shin-Okubo — strongholds of Korean culture in Japan.

Map of Zainichi Korean communities

Their story began with forced migration over a century ago, setting the stage for generations of struggle and resilience.

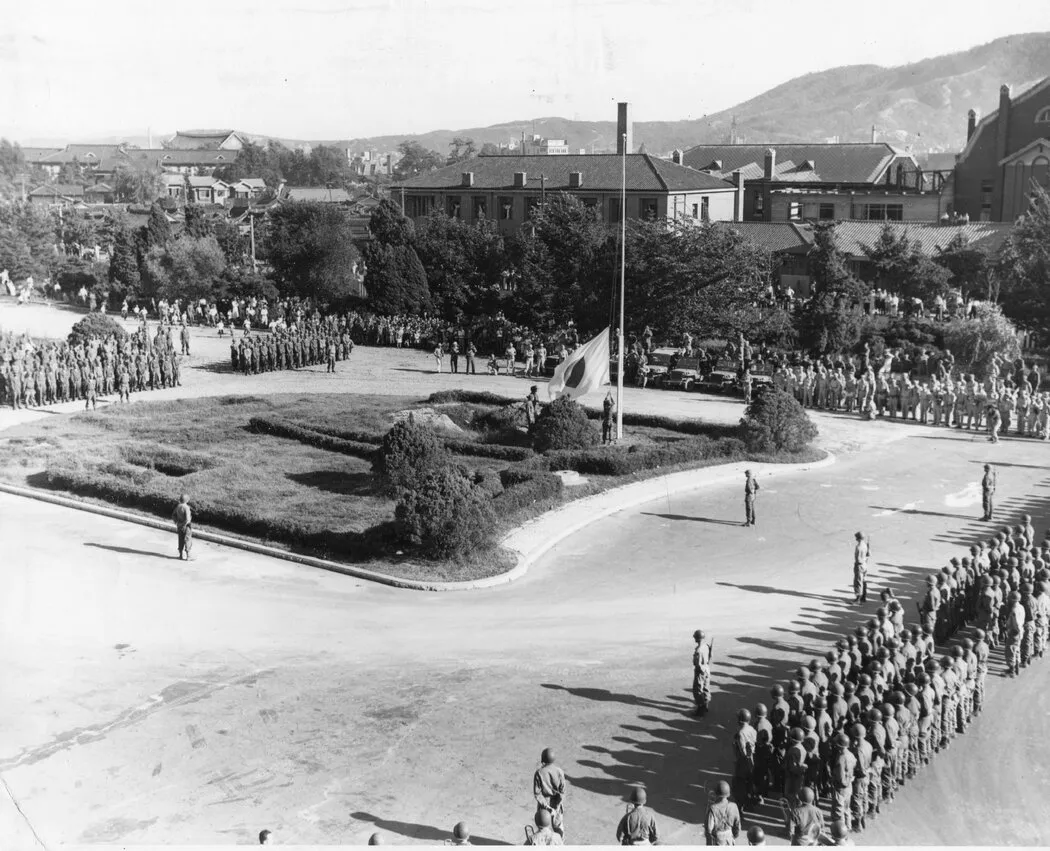

Colonial Roots: Leaving Home Under Pressure

Japan occupied Korea in 1910. Many farmers lost their land and crossed the sea to survive. During World War II, conditions became worse – hundreds of thousands of people were forced into mines and factories, many of whom never returned home. After Japan's defeat in 1945, Koreans hoped to return, but war and division left many stranded.

Japan was chaotic after the war. The government stripped Koreans of their citizenship and turned them into foreigners overnight. About 2 million people were making a living by working as day laborers, recycling,g or making illicit liquor. Discrimination was everywhere – jobs, housing, even violence – which left many people feeling hopeless.

A Divided Identity: Two Groups, Two Paths

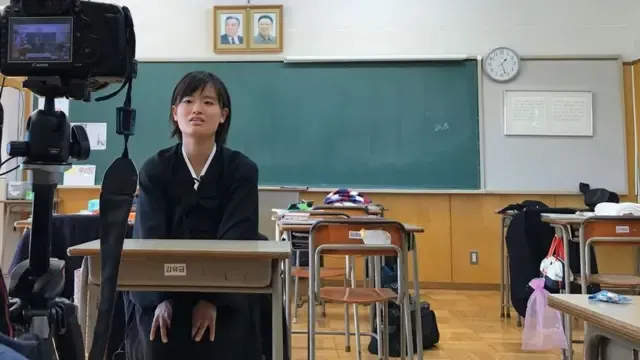

When Korea was divided in 1948, echoes of the division were also heard in Japan. Zainichi Koreans split into two camps:

- Mindon (pro-South Korea): approximately 300,000 members, working to strengthen ties with Japan and support fellow Koreans.

- Chongryon (pro-North Korea): approximately 100,000 members, running their own schools and cultural programs.

Clashes were common in the past, but the younger generation is slowly finding ways to talk and cooperate.

Students at a Chongryon school

The name remains a sensitive issue. During colonial rule, Koreans were forced to adopt Japanese names. Many people kept them after the war to avoid discrimination. Their Korean names represented identity, while Japanese surnames became tools of survival – a dual existence that shaped their lives.

Life Today: Between Two Worlds

Pass through Shin-Okubo in Tokyo or Tsuruhashi in Osaka and you might think you're in Seoul. Posters of K-dramas cover the walls, kimchi stalls line the streets, and BBQ smoke fills the air. These neighborhoods are cultural fortresses, bursting with energy.

Osaka’s Tsuruhashi district

To date, most Zainichi Koreans are third or fourth generation, born and raised in Japan. Many people are fully integrated into society. Some people, like Masayoshi Son, founder of SoftBank, have become prominent business leaders, inspiring the younger generation.

Special permanent residents enjoy rights beyond those of regular permanent residents:

- Unlimited stay without renewing visas.

- No restrictions on employment.

- Access to social security, pensions, and health care is almost equal for citizens.

- Re-entry permits are valid up to six years (regular residents get five).

- Deportation is extremely rare, requiring serious crimes and ministerial approval.

- No need to carry ID at all times, unlike other foreign residents.

However, life is not without worries. The biggest difference is political – special permanent residents cannot vote, not even in local elections. The United Nations has repeatedly urged Japan to give this right, but nothing has changed yet.

The struggle for identity also persists. Many people still use Japanese-style names in daily life, keeping their Korean names private within the family circle to avoid discrimination. Younger generations often choose to become Japanese citizens, with thousands doing so each year, primarily to secure easier opportunities for their children.

Discrimination has also not ended. Hate speech online and subtle barriers remain in the job market. While the rise of K-culture has encouraged young people to proudly use their real names and embrace their heritage, the wounds carried by older generations run deep.

Zainichi is a reminder of the Korean people's century-long colonial legacy and a symbol of coexistence. Many people say, "We are both Japanese and Korean." That dual identity reflects the reality of globalization, where relationships often span more than one country.

So the next time you're enjoying barbecue at Shin-Okubo or Tsuruhashi, take a moment to ask about the story behind the flavor. You can weave stories of resilience, struggle, nd hope into every particle.