Under Japan's national "Zero Illegal Migration Plan", Kawaguchi city in Saitama has become a hot spot. The region is home to many Kurds from Türkiye, and clashes with locals are growing worse. Disruptive behavior continues to be seen at convenience stores and other public places. At the same time, deportations are proceeding in dozens of batches, and once prominent figures in the Kurdish community were sent back, more people began to voluntarily choose to return. Change is slowly taking shape.

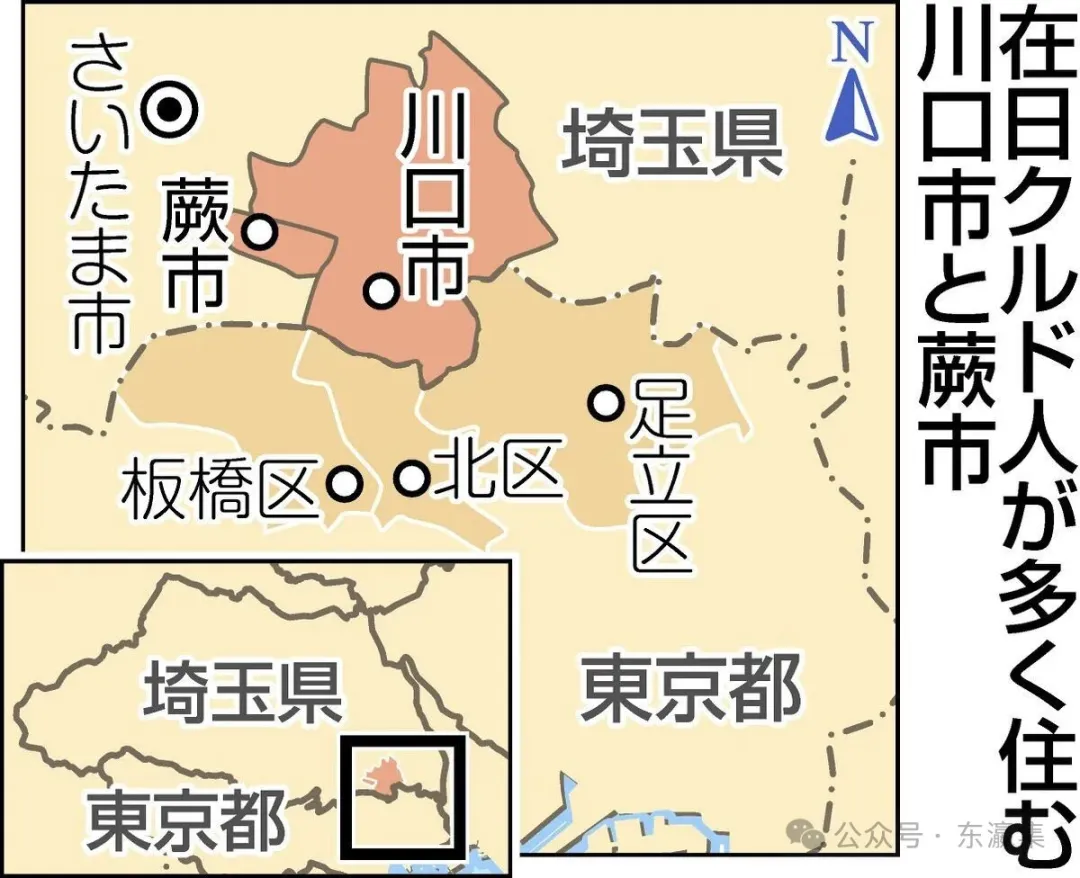

⬆ Location of Kawaguchi and Warabi

“What Did I Do Wrong?”

In North Kawaguchi, there is a convenience store next to a restaurant. This spring, a young clerk in his twenties told a group of Kurdish men to be quiet. Instead of listening, one of them pushed him away.

"I spoke politely, but it freaked him out. They roam the parking lot, smashing trucks, pulling up chairs on the loading dock, drinking and yelling. I thought about calling the police, but the cameras didn't catch it, so there's no proof."

A store owner in his sixties said the problem started around June last year. Complaints skyrocketed, with police arriving six times in a single night. By autumn, Japanese youth also began to join in, making the situation worse.

⬆ Kurds gathering in front of a convenience store

Groups of riders on motorcycles roar down the road, engines roaring. Some buy knives, some wave metal rods. When the police come, they say, "Somebody has tipped you off, go ahead." They stop before leaving and yell in broken Japanese, such as "Don't go back".

The owner continued, "If you say anything, someone throws a burning cigarette at your feet or yells in your face, 'What did I do wrong?' Neighbors who spoke found people urinating outside their doors."

A family who moved here three years ago with daughters in elementary and middle school finally gave up this August. He said, "We have crossed our limits," and walked away.

One resident sighs, "Not all Kurds are bad. But can you really live side by side with such people? That's the question." "Since the leader of that community was deported, things have calmed down a bit," he admitted.

⬆ Kurdish men flipping off police

A Mood of “Giving Up”

On 10 December, Japan's Immigration Services Agency reported progress under the Zero Illegal Migration Plan. Between June and August, 119 people who refused to leave were deported with an escort. Turks formed the largest group with 34 cases, 22 of them repeat refugee applicants.

A Kurdish man from Kawaguchi was standing outside. He ran a demolition company, appeared frequently in the media, and was seen as a leader. In July, he was deported from Narita Airport, marking a turning point.

⬆ Kurdish man deported

He had been living in Japan since 2004, in Kawaguchi for more than twenty years. Their refugee claims failed all the way to the Supreme Court. During that time, he remained on temporary release status.

Through family names, he ran his own company and hired fellow Kurds. He even donated one million yen to Saitama's fund, receiving a letter of thanks from Governor Motohiro Ono. His influence was huge.

After his deportation, locals noticed that things calmed down. Those who had opposed leaving now have a feeling of resignation.

Migration or “Immigration” Trend

In September, legislator Satsuki Katayama shared immigration data on her YouTube channel. As of the end of June, there were 2,146 Turkish citizens in Kawaguchi, 60 fewer than six months earlier.

Of these, 760 were with "specified activities" status in refugee application processes, down from 144. Another 707 were under deportation orders, down by 41. Breaking this down, 607 were on temporary release, while 100 were under new supervision measures.

Together, they made up 68% of the total, the majority of whom are considered Kurds. Thanks to deportations and voluntary returns, the share of refugee applicants dropped seven points from 75% six months earlier.

But as numbers declined in Kawaguchi, more Kurds moved into apartment complexes in the southern district of nearby Saitama city.

Meanwhile, spousal visas increased from 138 to 146, and family migration permits increased from 80 to 116. The trend toward compromise with legal status – what some call “immigration” – is clearly increasing.